Cornellians to Anatolia

Blizzards, bad roads and "unsettled" country: nothing daunted three Cornellians on an archaeological expedition to Anatolia in 1908. But their courageous story has been lost to Cornell history — until now.

The Beginning

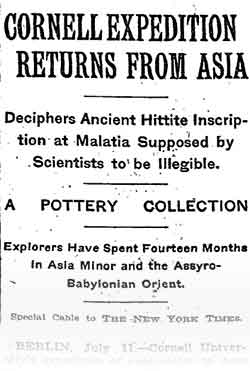

Blizzards, bad roads, an "unsettled" country: the challenges facing the three Cornellians who sailed from New York for the eastern Mediterranean in 1907 were legion. But their fourteen months' campaign in the Ottoman Empire nevertheless resulted in photographs, pottery, and copies of numerous Hittite inscriptions, many newly discovered or previously thought to be illegible. It took three years before their study of those inscriptions appeared, and while its title page conveyed its academic interest, it tells us nothing of the passion and commitment that made it possible. The story of the men behind the study and their adventures abroad has been lost to Cornell history–until now. Take a look at the people behind the names in the "Cornell Expedition to Asia Minor and the Assyro-Babylonian Orient."

Ambition and Organization

The organizer, John Robert Sitlington Sterrett, spent the late 1800s traveling from one end of Anatolia to the other, where he established a reputation as an expert on Greek inscriptions. In 1901 he became Professor of Greek at Cornell, where he instilled his own love of travel in his most promising students. For Sterrett, the expedition of 1907-08 was only the first step in an ambitious long-term plan for archaeological research in the Eastern Mediterranean. In his own words, he planned to answer the "call of humanity at large for light in regard to the life of man in the cradle of Western civilization." (Sterrett's "Plea" of 1911)

Meet the Explorers

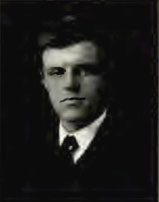

To launch his plan, Sterrett selected three recent Cornell alums. Their leader, Albert Ten Eyck Olmstead, already projects a serious, scholarly air in his yearbook photo of 1902, whose caption jokingly alludes to his freshman ambition "of teaching Armenian history to Professor Schmidt." In 1907, just before crossing to Europe, Olmstead received his Ph.D. from Cornell with a dissertation on Assyrian history. Olmstead's two younger companions, Benson Charles and Jesse Wrench, were both members of the class of 1906. They had spent 1904-05 traveling in Syria and Palestine, where they rowed the Dead Sea and practiced making the "squeezes," replicas of inscriptions made by pounding wet paper onto the stone surface and letting it dry, that would form one the expedition's primary occupations.

Olmstead, Wrench, and Charles made their separate ways to Athens, whence they sailed together for Istanbul. Much of their time in the Ottoman capital was spent purchasing provisions and hiring porters. The trip's employees would do much more than carry the baggage. Solomon, an Armenian from Ankara, had a knack for quizzing villagers regarding the location of remote monuments. At the end of the trip, he "at once entered the service of a German archaeologist."

While preparing for the journey, the group made smaller trips in western Anatolia. At Binbirkilise, a Byzantine site on the Konya plain, they visited the veteran English researchers Gertrude Bell and William Ramsay. Bell jotted down her London address in Wrench's fieldbook, while Ramsay and Olmstead argued about the height of Kara Dağ, "the black mountain." As Ramsay later remarked laconically, "it was a matter of aneroids."

Like Bell, whose Byzantine interests set her at the vanguard of European scholarship, the Cornell researchers were less interested in ancient Greece and Rome than in what came before and after. Their particular focus was on the Hittites and the other peoples who ruled central Anatolia long before the rise of the Hellenistic kingdoms. When the expedition set off in mid-July, their starting point was not one of the classical cities of the coast, but a remote village in the heartland of the Phrygian kings. As Wrench later recalled, "there were our clean new tents, with American and Turkish flags flying, pitched in the pretty little valley in which is Demirli."

Tracing the Route

A Royal Squeeze

When the expedition reached Ankara, a sleepy provincial town decades away from becoming the capital of the Turkish Republic, they set to work on its greatest Roman monument, the Temple of Augustus, on which was displayed a monumental account of the deeds of the deified emperor. No squeeze had ever been taken of this "Queen of Inscriptions." The job took over two weeks, and the 92 sheets made it safely back to Cornell. They have now been digitized and are available to scholars on the Internet as part of the Grants Program for Digital Collections in Arts and Sciences.

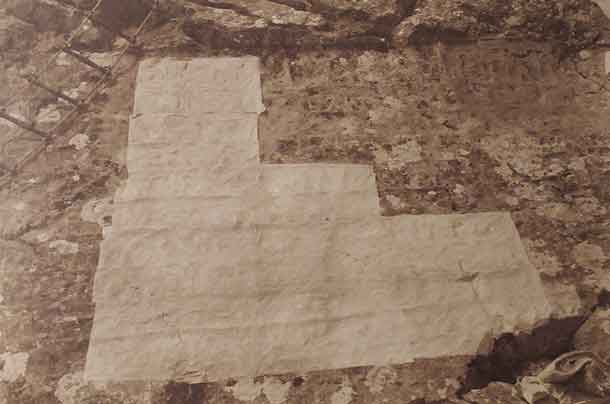

Still, the travelers reserved their greatest enthusiasm for the much older inscriptions of the Hittite kingdoms. Their first major achievement came at the Hattusha, site of the Hittite capital, where they set to work on a hieroglyphic inscription of six feet in height and over twenty feet in length, known in Turkish as "Nişantaş" (the marked stone). The inscription was widely believed to be too worn to be read, but the expedition "recovered fully one half. "Their dedication is all the more remarkable as the script in which it is written, now known as "hieroglyphic Luwian," was not deciphered until over half a century later. We now know that Nişantaş celebrates the deeds of Shupiluliuma II, last of the Great Kings of Hattusha.

Triumph in Ice and Snow

As the expedition pushed eastwards, and the fall turned to winter, the Cornellians began to worry that the snows would prevent them from crossing the Taurus mountains, trapping them on the interior plateau. While Wrench and Olmstead pushed ahead with the carriages along the postal route, Charles led a small off-road party to document the monuments of the little-known region between Kayseri and Malatya. A grainy photograph taken at Arslan Taş, "the lion's stone," shows two figures bundled against the cold, doggedly waiting for a squeeze to dry.

The backstory is recorded in the expedition's journal. It was early afternoon on November 6th, 1907, before Charles found a villager who could show him the site of the inscribed statue. They made a strenuous hike up a mountain "through a fall of snow so thick that one could see only a rod or two in any direction." Once they arrived, the squeeze "froze as soon as on and refused to dry although we built a fire just in front. Finally darkness began to come on and we were obliged to remove the squeeze in order to dry it over the fire. Then, in the darkness ... we descended the mountain." Back in the village, dinner was served, "a steaming dish of wheat pilaf .... Many of the children, in their quick, wide awake manner of replying to jokes or bantering, reminded me strongly of young Americans." It was the last night of Ramadan, and on the next morning the villagers celebrated with their guests. "At last the chief poured out the good black coffee for all to drink. We drank and after a hurried breakfast went out into the snapping cold of a world of snow and ice."

A Narrow Escape

The expedition beat the worst of the snows and was in the lowlands of northern Mesopotamia by December. As they made their way to the regional center, Diyarbakır, they heard that the city was in revolt: the local worthies had occupied the telegraph office to protest the depredations enacted by a local chieftain. The travellers were a day's march behind the imperial troops who had been sent in to quell the rebellion, and who frequently left the roadside inns in a deplorable state. When they arrived in Diyarbakır they found the "streets of the city filled with soldiers" and looked on as the imperial "peace commission" arrived from the south: "the Aleppo road was lined for more than a mile with soldiers and civilians accompanied by large numbers of women and children."

From Archaeology to Architecture

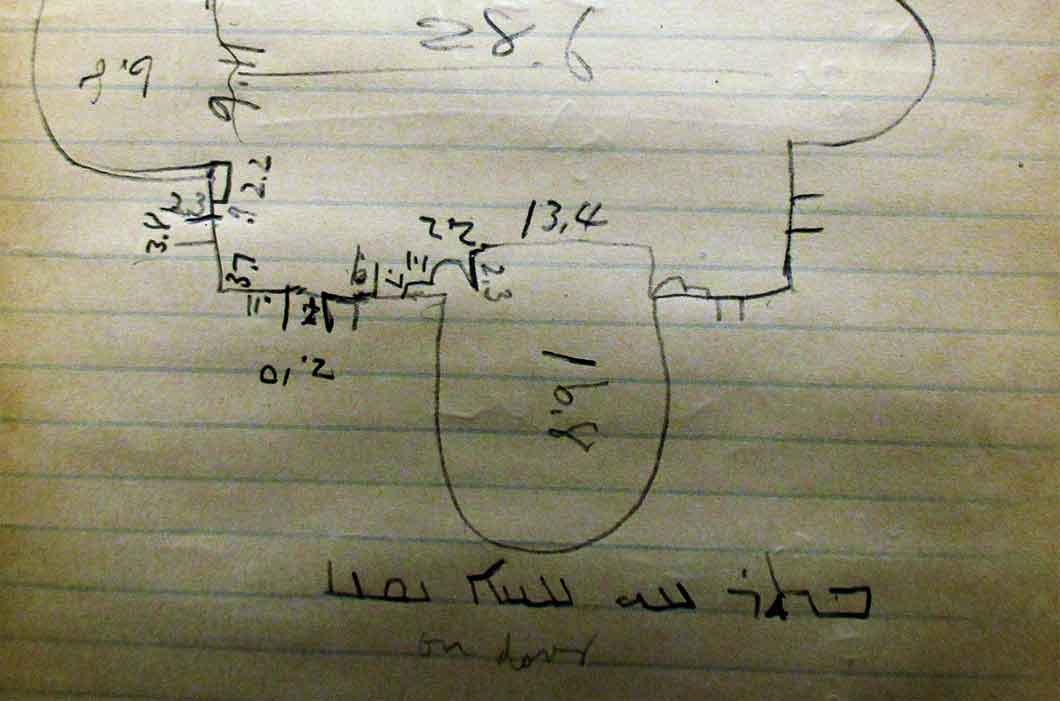

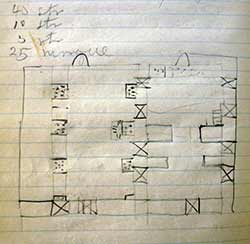

As the expedition moved out of the Hittite heartlands, we begin to see in Wrench's fieldbooks the beginnings of a new interest in the medieval architecture of the Syriac-speaking Christian communities. The first drawing to appear in his notes is a hastily-sketched plan of the early medieval Deyrulzafaran, "the saffron monastery," located outside of Mardin. Underneath he has copied the Syriac inscription that he found above the door. A few days later and a few pages further, we find a drawing of the late antique church of Mar Yakub in Nusaybin. When, in the following year, Wrench made his way back to Istanbul, he took a long detour through the Tur Abdin, the heartland of Syriac monasticism.

The Final Push

The expedition frequently visited American missionaries along their route, celebrating Christmas in Mardin with the local mission of the American Board in Turkey. But as they pressed on across the steppes that today form the far northeastern corner of Syria, the strains of six months' steady travel began to show. On New Years' Eve they pitched their camp in a driving rain while their Kurdish escort "sang a chant which sounded exactly like one used in the Syriac church. On inquiry, we learned that this was done to close the mouths of the wolves."

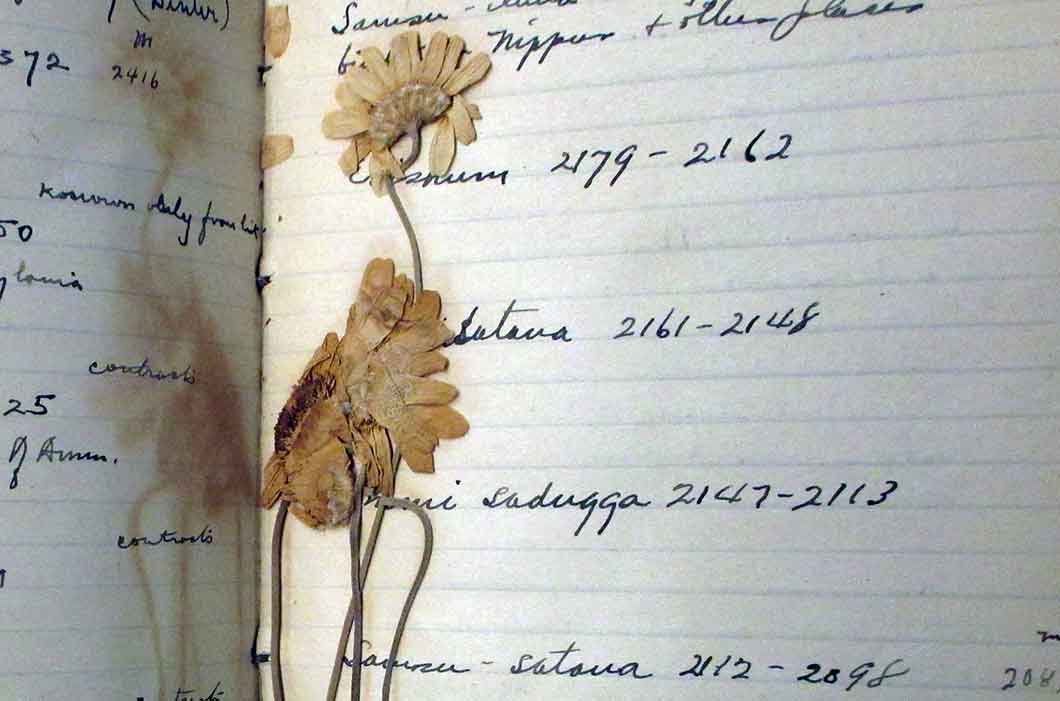

The travellers gained one last burst of strength in the new year, as they visited the great Mesopotamian sites of Nimrud and Nineveh. Wrench supplemented his notes on the "first Babylonian dynasty" with a clutch of pressed flowers. But on the final stage, the carriage that carried their bedding tipped into the river, and it was a soaked and bedraggled company that arrived in Baghdad on February 7th of 1908. They had covered over 1,500 miles since setting out from Demirli 206 days before.

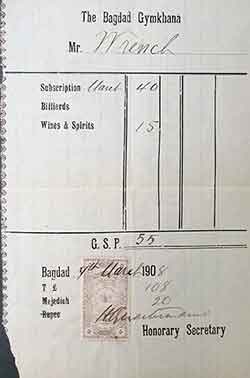

Raise a Glass

Baghdad in the early twentieth century was a lively international city, and as the company recuperated they took advantage of its entertainments. On February 22nd they logged a long evening at the club, dancing and leading a round of the Cornell Yell. Their bar tab is preserved at Kroch Library. From Baghdad the travellers followed separate courses back to Istanbul, where they would reunite once more in June. There a letter awaited Wrench from George Lincoln Burr, the university librarian and professor of medieval history. Wrench had written to Burr several months earlier, from Aleppo, as he anxiously began to consider his future back in America. Burr's advice was both honest and sanguine. It was not possible to pursue a career in "pure research," but teaching was a noble profession that did not entail "any loss of a scholar's self-respect." He continued: "Not that I think you will ever regret, whatever the hardships, unless your health be broken by it, your experience as an explorer. It will be to you a mine both of knowledge and of anecdote all your life long."

And After

Back in the States, the three members of the expedition continued to follow different paths. Charles defended his study of the Hittite inscriptions for his Ph.D. at Penn, where he taught for a few years before leaving the academy to take up carpentry. Olmstead came very close to a life of "pure research," taking a position at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago and publishing widely on ancient history. The mature scholar looked much the same as the young graduate. In the Jesse Wrench of 1929, on the other hand, we see a very different person from the yearbook photo of 1906. Wrench took Burr's long-distance advice to heart, and pursued a decades-long career as a beloved teacher of history at the University of Missouri. There he advised a branch of the Turkish-American society, Dostluk ("Friendship"), and was a lifelong member of the NAACP.

The three men continued to work together, but their planned narrative of the expedition was never published. As a result they have been largely left out of the early history of American archaeology in the eastern Mediterranean. But with the help of the journals and notebooks that they left behind them, we can now see that they left a distinctly Cornellian stamp on the tradition of the archaeological voyage: unorthodox, open-minded, and unafraid of the snow.

Acknowledgments: Research on the Cornell Expedition is being conducted by Benjamin Anderson, Assistant Professor of the History of Art, and Eric Rebillard, Professor of Classics. Funding has been provided by the College of Arts and Sciences, the Department of Classics, and the Department of the History of Art. Special thanks to Nicholas Lashway, M.A. student in the Cornell Institute of Archaeology and Material Studies, and William "Zelli" Fischetti, Assistant Director, the State Historical Society of Missouri Research Center – St. Louis.