The Vietnam War on Campus, Revisited

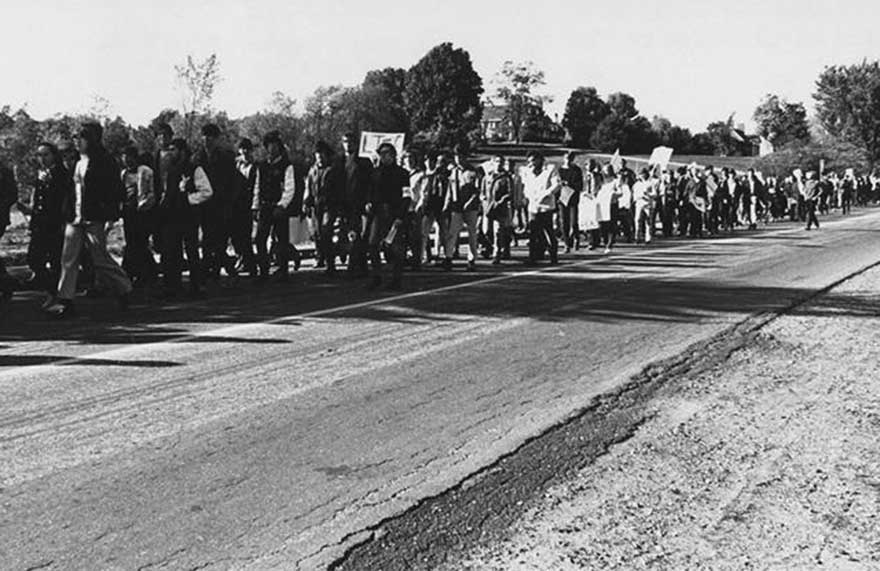

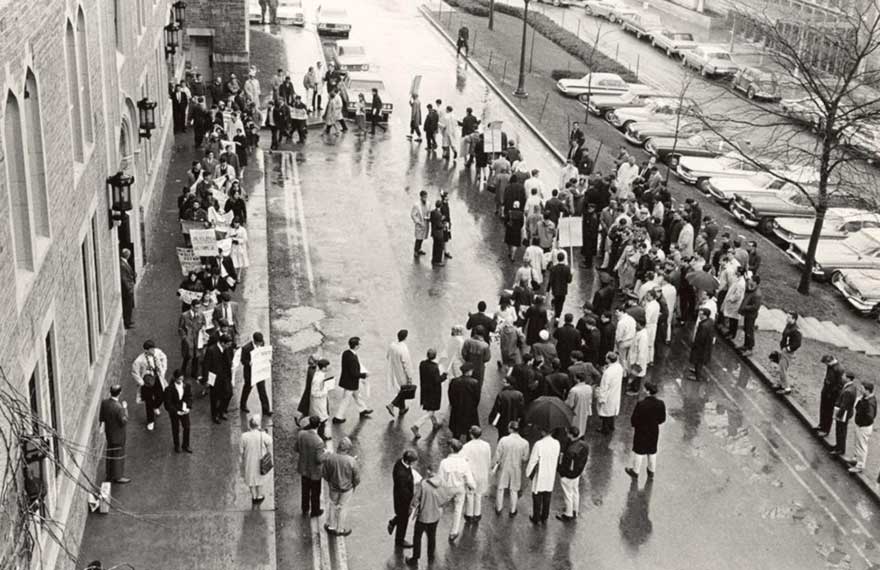

In the mid-1960s, Cornell students were caught up in the cataclysmic movements and events surrounding the growing resistance to the Vietnam War.

The Vietnam War on Campus, Revisited

In the mid-1960s, Cornell students were caught up in the cataclysmic movements and events taking over the country, especially the growing resistance movement against the Vietnam War.

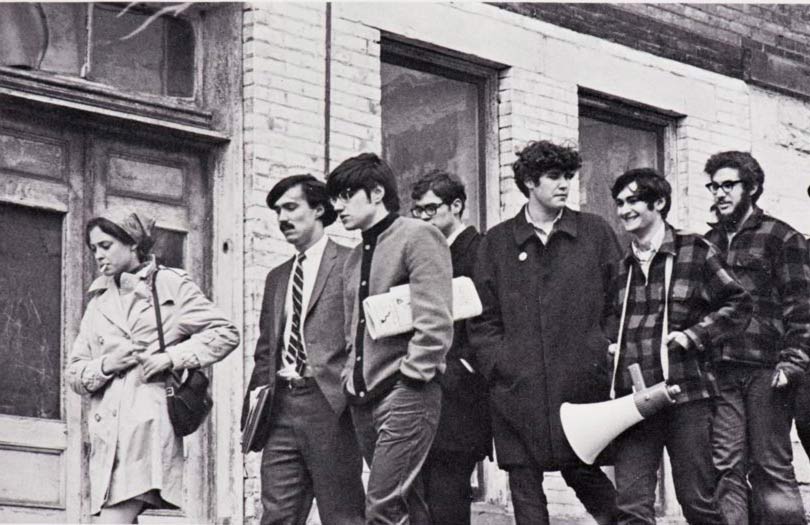

Bruce Dancis was a freshmen primed for activism as a participant in the 1963 March on Washington. Sheila Tobias was an administrator in Day Hall who joined a band of anti-war faculty and graduate student activists. David Connor was an assistant Catholic chaplain with Cornell United Religious Work who educated faculty and counseled students trying to avoid the war. And Frank Dawson was an African-American student who tried to balance his activism with his mother's fears as a first-generation college student wanting to protect his future.

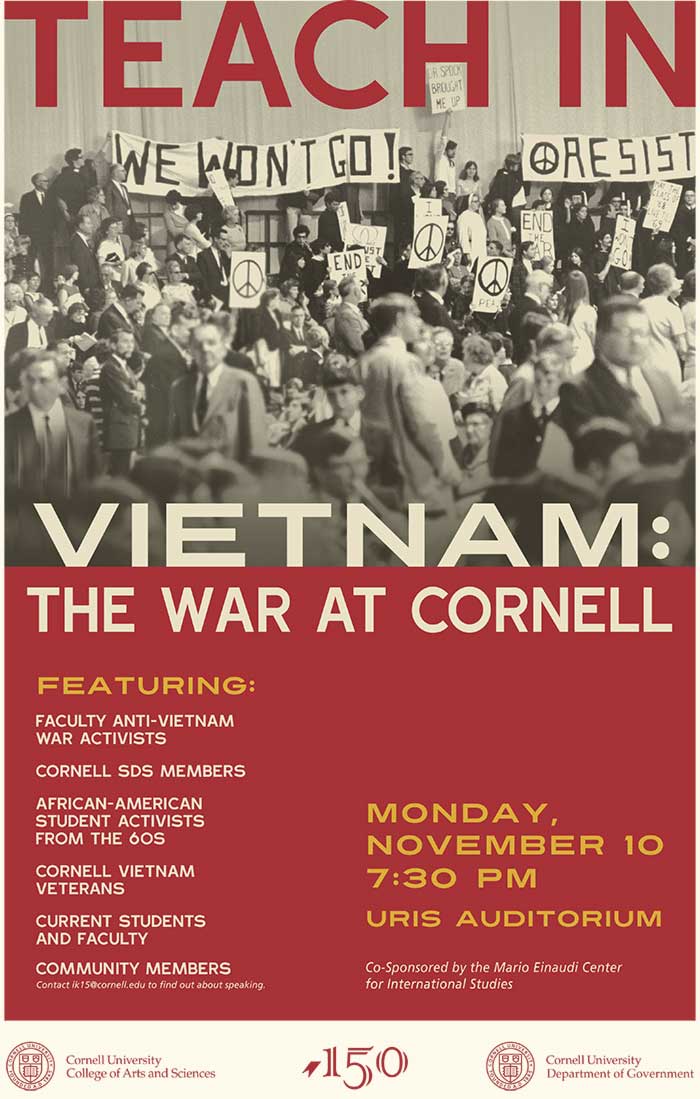

All of them worked together to form a new Left, a group that occupied buildings, held protests, scheduled Teach-Ins and destroyed their draft cards to protest the war in Vietnam and push for civil and women's rights.

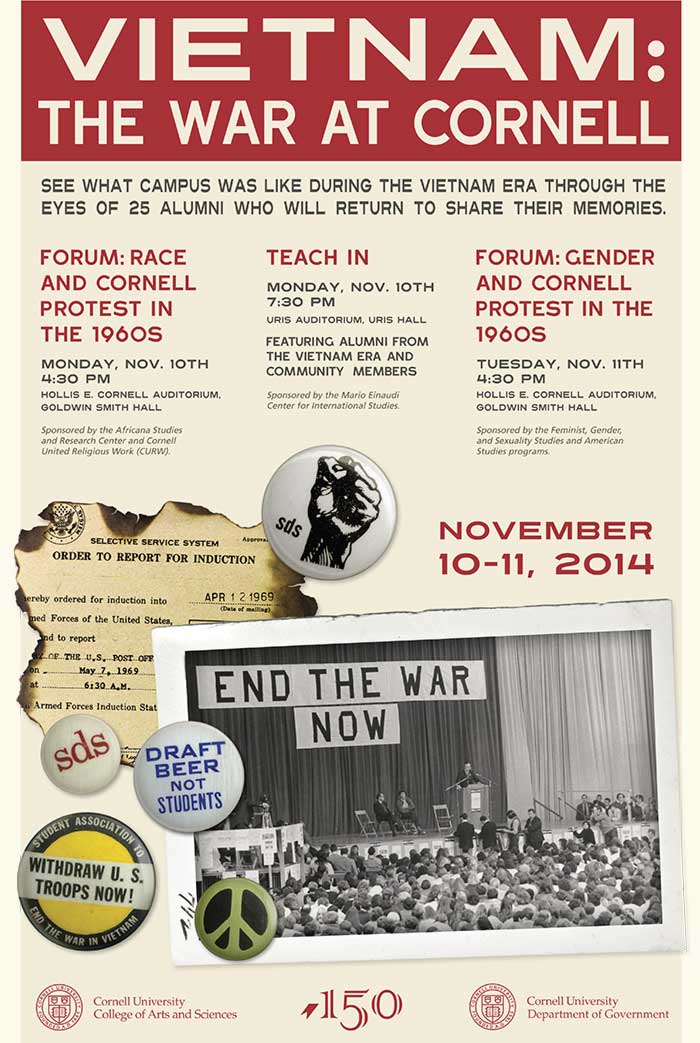

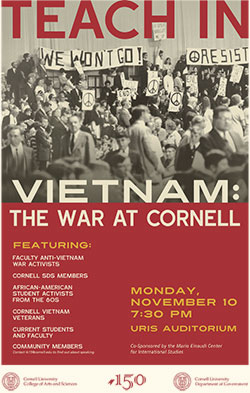

Twenty-five of these students, faculty and staff will return to campus Nov. 10-11 for a 50th anniversary reunion, organized by Professor Isaac Kramnick, the Richard J. Schwartz Professor of Government as part of the Department of Government and College of Arts and Sciences' celebration of the university's sesquicentennial.

Student Radicals Unite on Anti-War Messages

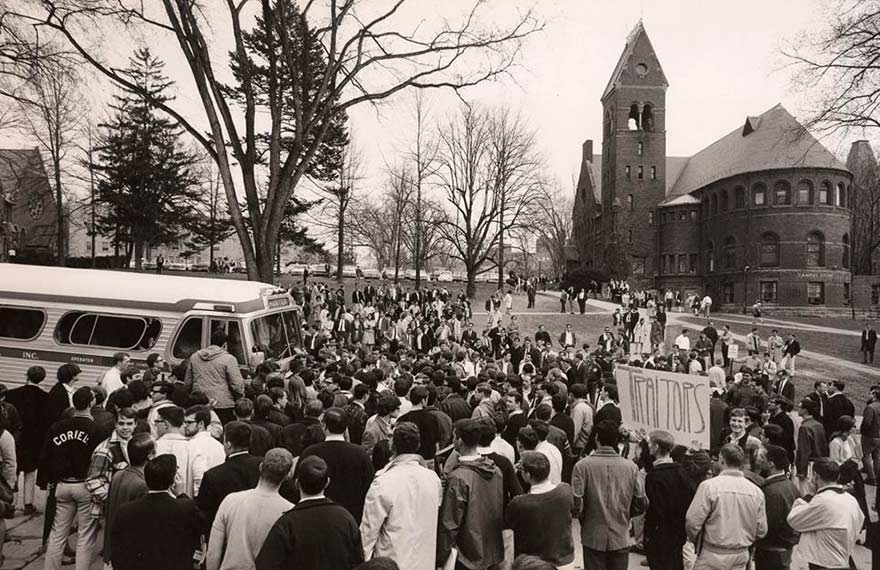

During this era, Dancis and other students – many of them members of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) – helped put Ithaca on the map alongside Berkeley and Ann Arbor as the epicenters of student opposition to the war.

"I probably helped turn the heat up, but I certainly didn't start things," said Dancis, who came to campus as a freshman in the fall of 1965. Earlier that spring, a student-faculty ad hoc committee on Vietnam had been formed, busloads of Cornellians and community members attended anti-war rallies in Washington, D.C. and a May teach-in brought more than 2,000 people to Bailey Hall.

When Dancis arrived, he helped to form a Cornell chapter of SDS that first fall and took part in protests about the requirement that universities release class rankings to draft boards and administer selective service exams that could result in revoked student deferments. As a sophomore, Dancis gained prominence as the first Cornell student to destroy his draft card.

"I felt I couldn't accept my student deferment," Dancis said. "I was a middle class kid who was expected to go to college. My parents could afford to send me. What about all of those kids who weren't in my situation?"

But his draft card "was burning a hole in my pocket," he said of the Dec. 14, 1966 event in front of Olin Hall, where he destroyed his draft card while university administrators sat inside debating Cornell's selective service policies. Dancis eventually dropped out of Cornell to lead draft resistance movements in both Ithaca and New York City

"My goal was to build a movement large enough, with so many men resisting the draft that we would fill the courts and the jails and the U.S. Army would have a hard time finding enough men to go to Vietnam," he said. But he found that many of the resisters weren't prosecuted – only two of the 50 + draft resisters in Ithaca ever spent time in jail, he said. Dancis spent 19 months in federal prison.

Still, Dancis said Cornell's movement had an impact on the country, with anti-war candidates winning national seats, public opinion polls swaying against the war and politicians eventually voting to stop funding the South Vietnamese. Dancis ended up with a bachelor's from the University of California, Santa Cruz, a master's in American history from Stanford University and a career in journalism.

Helping Resisters Find a New Life in Canada

Chaplain David Connor was active in the movement at the same time, testifying in Dancis' trial and helping students find ways to avoid the draft, sometimes by filling out paperwork and sometimes by finding them new identities and helping them get to Canada.

"Things were breaking on many fronts," Connor said, adding that civil rights and women's rights issues were also coming to the forefront. "I was lucky enough to be in a place to do something about it and I took a shot."

Connor, a former Cornell football player, said his position as chaplain allowed him to work with faculty, staff and students. "Fraternities and faculty members would invite me over to talk because they didn't understand the anti-war movement," he said. "They couldn't understand how the greatest country in the world could be as bad as the peace movement and the SDS was portraying it to be."

Connor, who was 30 at the time, ended up mailing his own draft card back to his local board. He was immediately called for induction and showed up at the Buffalo, N.Y. induction center along with a number of students, refusing to be inducted. Charges against him were dropped and he eventually left the priesthood, founded a commune close to Ithaca and worked for various peace and social justice causes here until 1989, when he moved to Vermont. There, he recently served as associate pastor for The Old Meeting House church before retiring. He is involved with several peace and justice organizations, has demonstrated at marches for peace in Washington, New York and in Vermont and has attended a weekly Peace Vigil every Friday at noon for 12 years in front of the Montpelier Post Office.

An Ally From Within Day Hall

Sheila Tobias – newly hired in 1967– was actively opposing the war in Vietnam as a young faculty member at the City College of New York before coming to Cornell.

"[At CUNY] we were stressed by our students' dilemmas: draft card burners who risked going to jail - and those whose lives were in our hands because if they failed our courses they lost their student deferment," she said. "One year a group of us in the history department gave all A's to all our students as a protest. But of course that only sent more underprivileged students to the war."

Once at Cornell, she said she was attracted to Daniel Berrigan and joined the "Dump Johnson" movement after hearing Allard Lowenstein on campus urge Democrats to oppose the president's likely re-nomination.

Her position in Day Hall led some anti-war activists to believe she would unlock the doors for their sit-ins, which she did not do, although she did support them in many other ways.

"I was not an official adviser to Cornell students," Tobias said, "but because I was permitted to 'assist' as a section leader in a popular freshman-sophomore history course, I knew a bunch of students and was drawn with them to several on-campus anti-war rallies."

Tobias said a number of faculty, especially those in the humanities, provided important leadership to protestors, but many others were opposed.

"I experienced close at hand the passion for ending the war and the resistance to the resisters," she said of the mixed feelings on campus. "But we activists took full advantage of Cornell facilities, notably Clark Hall (built with Department of Defense money) to do our xeroxing."

Between protests and draft-card burnings, Tobias said, student activism brought together anti-war activists in the Ithaca community, especially those already involved in the Glad Day Press, which published broadsides and pamphlets for the community and the nation.

Tobias said she "cut her teeth" with the anti-war and civil rights movement before taking on the cause of women's rights, eventually founding a women's studies course, which in turn launched the Women's Studies program at Cornell – one of the first in the nation. She then moved into research on undergraduate education in math and science and is the author of numerous books on math avoidance and reforming college science, including "Overcoming Math Anxiety," "Breaking the Science Barrier," and "Rethinking Science as a Career," as well as books on feminism such as "Women, Militarism, and War" and "Faces of Feminism: An Activist's Reflections on the Women's Movement."

Activism on Many Fronts

"I didn't consider myself a very political person at that time," said Frank Dawson, who arrived in Ithaca as a freshman in the fall of 1968 from New York City. "Activism wasn't even on my radar."

But the Afro-American Society had sent him a letter the summer before his freshman year. Dawson learned more about campus rights issues and became involved. "I didn't want to go to 'Nam' and I knew that many of my friends back in the projects were going," he said. "It was unfair that my friends were being drafted and sent away, but many things were also unfair at Cornell."

Dawson took part in every protest set up by the Afro-American Society.

"I was very impressed by the black upperclassmen that had experience dealing with this environment," he said. "They knew what needed to change, and they needed the brash incoming freshmen to make it happen."

But Dawson said for students like him – first generation college kids – there was always a risk in getting involved. You could lose a future you'd worked so hard to secure if you got arrested or kicked out of school.

Dawson, who became a media executive at CBS and Universal, and then a professor of communication and media studies at Santa Monica College, has captured this era at Cornell and other universities in a new documentary, a part of which will be shown during the Vietnam event on campus.

"Agents of Change: Black Students and the Transformation of the American University" was co-produced by Abby Ginzberg '71 and Dawson and tells the story of the Willard Straight takeover and similar events at campuses across the country.

"One of the greatest things about being at Cornell at that time was what happened outside of the classroom," Dawson said. "The discussions, dialogues and debates that went on forged in a me a focused lens through which I've considered everything for the rest of my life."

The feeling is mutual among his classmates, Dawson said. "People have gone into various careers –doctors, lawyers, poets, educators – but everyone was really shaped in some way by their involvement on campus at that time."

What Students Are Doing Today

Daniel Marshall '15, a resident of Telluride House and an assistant to Kramnick in organizing the project, said his interest in this time period began in 2012 when he read "Cornell '69" by Donald S. Downs about the Willard Straight Takeover.

Through the book, he was drawn to the story of the Barton Hall Community, "the occupation of Barton Hall by thousands of students and faculty who were acting in support of the Afro-American Society's demands from within the Straight," he said. "The occupation turned into a mass democratic assembly, passing resolutions and making decisions about what actions to take."

The description reminded Marshall of his own experience participating in the Occupy Wall Street movement. "The descriptions of the Barton Hall Community captured my imagination precisely because they articulated my experience of possibility, solidarity, and rupture."

Marshall said he's not a fan of discussing issues in terms of a "generation," but does think that students (as well as working-class people, people who are unemployed, immigrants and indigenous communities) are coalescing around issues they feel strongly about, in ways similar to activists of the 1960s.

Kramnick notes that Marshall is an exception. "Most students at Cornell are generally apolitical," Kramnick said. "Meeting with these 60s activists will make it clear to them that political commitment is not incompatible with a successful career, that, in fact, it can help shape and ground that career."

Marshall is a history major whose honors thesis will focus on the memory of Cornell 1969. "It's interesting because you can see the traditional pattern of youth political engagement re-emerging," he said. "You have horrific injustices going on all over the world, and when young people measure that suffering against the complicity of their own institutions, it's only a matter of time before they try to change those institutions."

He hopes alumni returning for the November event can speak about the conditions that caused them to get involved and to stay involved.